KHR Architecture since 1946

KHR Architecture was founded in 1946 by Gunnar Krohn and Eigil Hartvig Rasmussen, who knew each other through their spouses, who were also architects. Read the full story here.

Foundation

KHR Architecture was founded in 1946 by Gunnar Krohn and Eigil Hartvig Rasmussen, who knew each other through their spouses, who were also architects. Eigil Hartvig Rasmussen ran his own design studio, where he participated in competitions and won a number of prizes. Eigil Hartvig Rasmussen was quiet, intelligent and analytically gifted. A friendly and inclusive man, his attentive and stubborn nature bore fruit both when it came to the architectural competitions and when it came to hiring the right people for the firm's projects.

Gunnar Krohn, nine years younger than Eigil Hartvig Rasmussen, was a progressive and talented architect who worked for C.F. Møller in Aarhus and won a few competitions on his own. It was also he who initiated the collaboration that has since become KHR Architecture.

This is how the two architects are described in the article Between the clicking cranes, written by architect and researcher Birgitte Louise Hansen on the occasion of KHR's 70th anniversary in 2016.

Krohn & Hartvig Rasmussen's first joint project

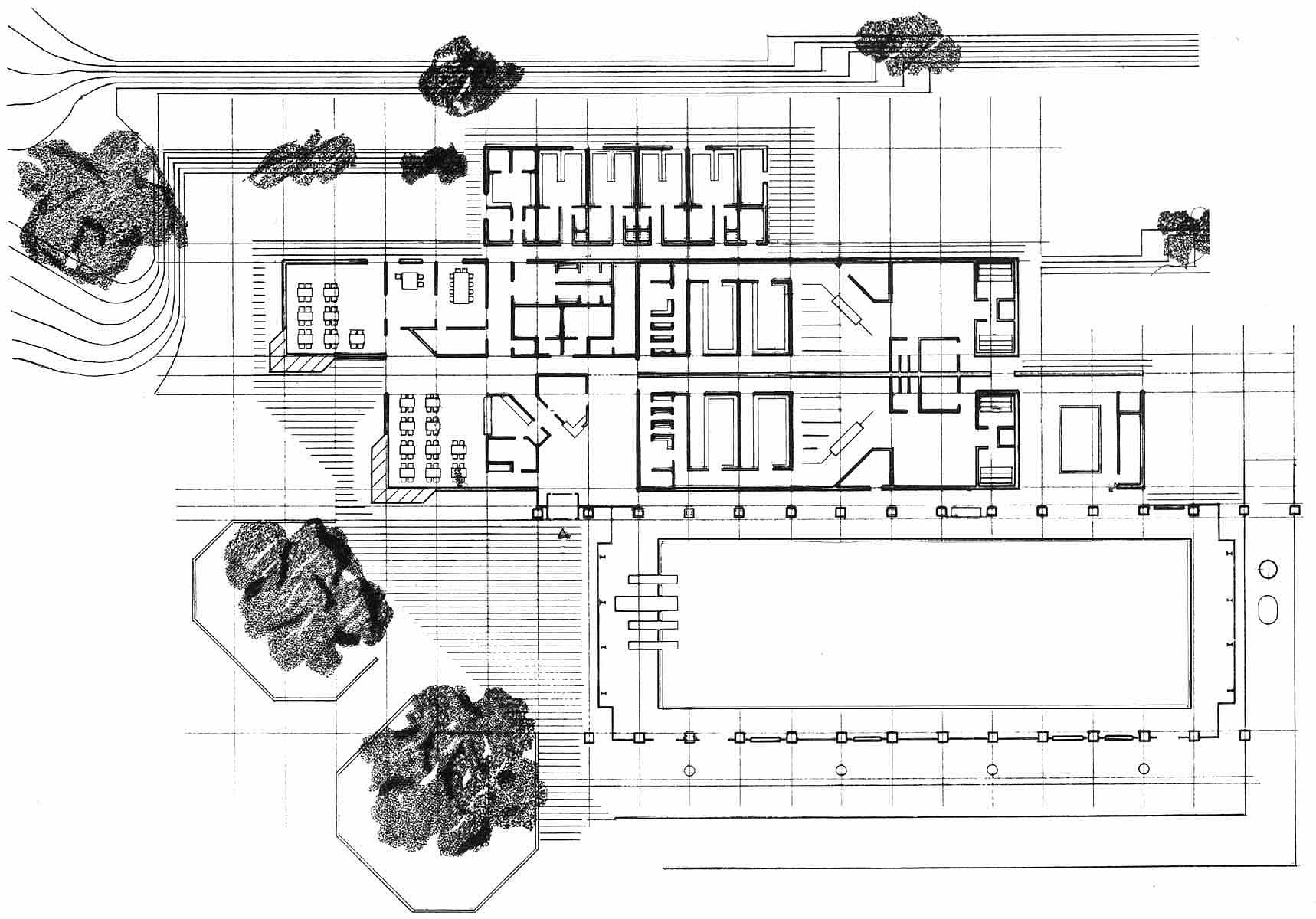

Gunnar Krohn wanted to participate in a Scandinavian architectural competition in 1946. It was about a plant for the machine factory Atlas, and together with Hartvig Rasmussen he designed and won the competition. This project was the starting point for the collaboration between the two architects.

In 1950, Krohn & Hartvig Rasmussen set up a joint design studio on Købmagergade in Copenhagen. Gunnar Krohn had an office in the fine, bright rooms facing the street, while Eigil Hartvig Rasmussen sat in the rear rooms in the dark, which said a lot about the personalities and roles of the two architects in the firm. Krohn was an extrovert who worked relationally out of the office, while the more introverted Hartvig Rasmussen worked deeply and diligently on projects.

The open design principle

It was Gunnar Krohn who started the design of Atlas, while Eigil Hartvig Rasmussen was busy with tasks at his own design office. Architect Paul Berg was therefore hired as a collaborator and supervisor on the task.

In the post-war period, the welfare society was growing explosively and there was a great need to build housing, factories, hospitals and schools. The great dreams and expectations for the future also characterised the design studio.

Krohn & Hartvig Rasmussen developed the idea of the open construction principle for the Atlas building. Inspired by industrial construction in the United States, the ambition was to create a one-storey building with open large-space constructions that created the flexibility needed for more and simpler expansion options. The building system can be described as a game of blocks stacked on top of each other, and the Atlas factory was erected in just 10 days due to the simple tectonics.

Signature of the drawing office

The open construction principle, due to its uniform nature and standard forms, also became applicable in a number of Krohn & Hartvig Rasmussen's subsequent commercial projects, including the office hall for Copenhagen's Engros Grønttorv designed and built in the period 1951-1958 and the calculator factory Contex from 1952.

The principle became almost a signature for the design studio, which also designed Rødovre Centrum and Magasin Du Nord in the 1960s. Here, the idea of large, flexible spaces was further developed, just as the firm, with the design and construction of Lyngby Storcenter from the early 1970s, became skilled at designing huge structures that could function on commercial terms.

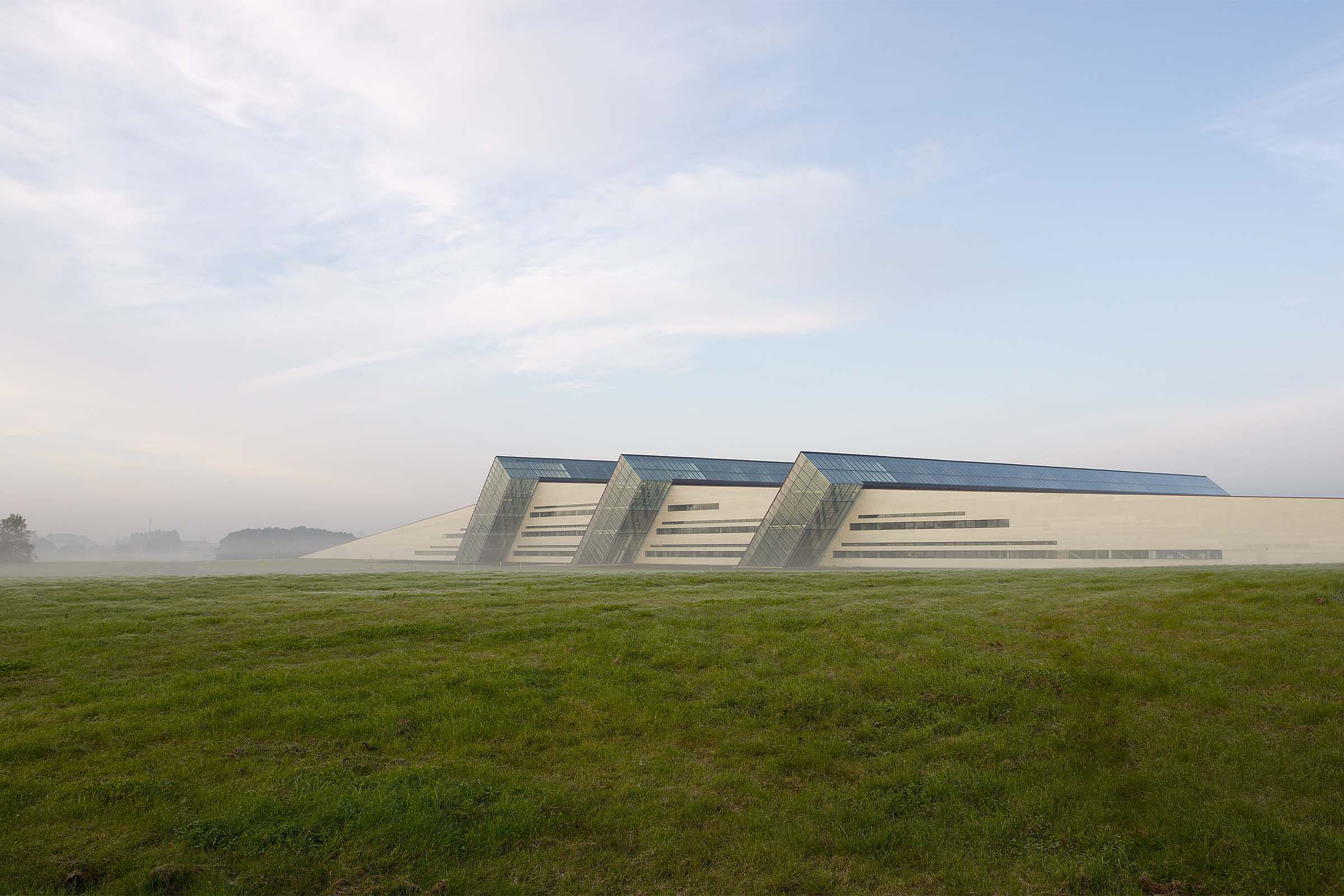

The open construction of the 50s has characterized the studio ever since, when also the extension of Billund Airport in 2002 and the factory Fiberline Compositecompleted in 2008, is built as large, column-free spaces that offer complete freedom and flexibility.

A divided design studio

Throughout the 1960s, the studio grew, but Gunnar Krohn and Eigil Hartvig Rasmussen's ideological differences shaped the studio, which almost split in two.

Paul Berg, who had been with the company since Atlas was built, became a partner, followed by Gunnar Gundersen, Bent Nielsen and John Ryde, who had all been with the company since the late 1950s. During the same period, the firm moved from Købmagergade to the Langebjerg apartments in Nærum, which had the flexibility needed to accommodate the cultural divisions that were emerging.

A new standard for healthcare buildings

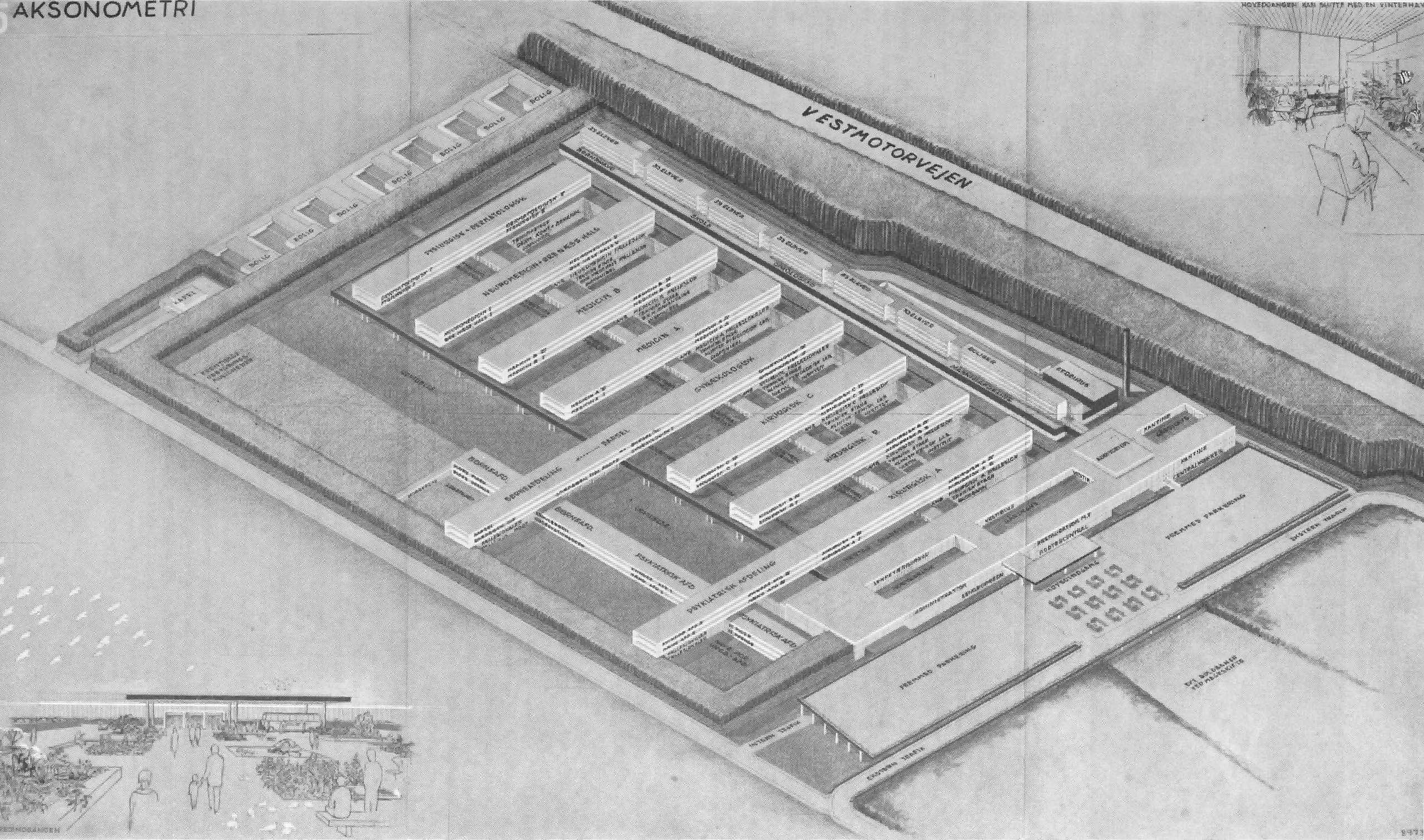

In the 1960s, the firm made its mark in the field of healthcare construction, where Krohn & Hartvig Rasmussen won an open competition in Norway for Bergen Hospital, which today stands side by side with the Children's and Adolescent Hospital, which KHR has been working on since 2006 until today.

After Bergen Hospital, the design studio won the new municipal hospital in Hvidovre, which set a completely new standard for hospital construction. Eigil Hartvig Rasmussen designed a horizontal hospital that stood out from the classic high-rise buildings. Bedrooms were on the second floor, and the treatment section in the living room opened up to the landscape, creating relationships between outside and inside and drawing the context into the architecture. This thinking has continued in the firm's projects ever since, with both Bispebjerg Hospital and the new Sct. Hans Retspsychiatry are designed and built as horizontal buildings that relate to the landscape.

New forces for the design studio

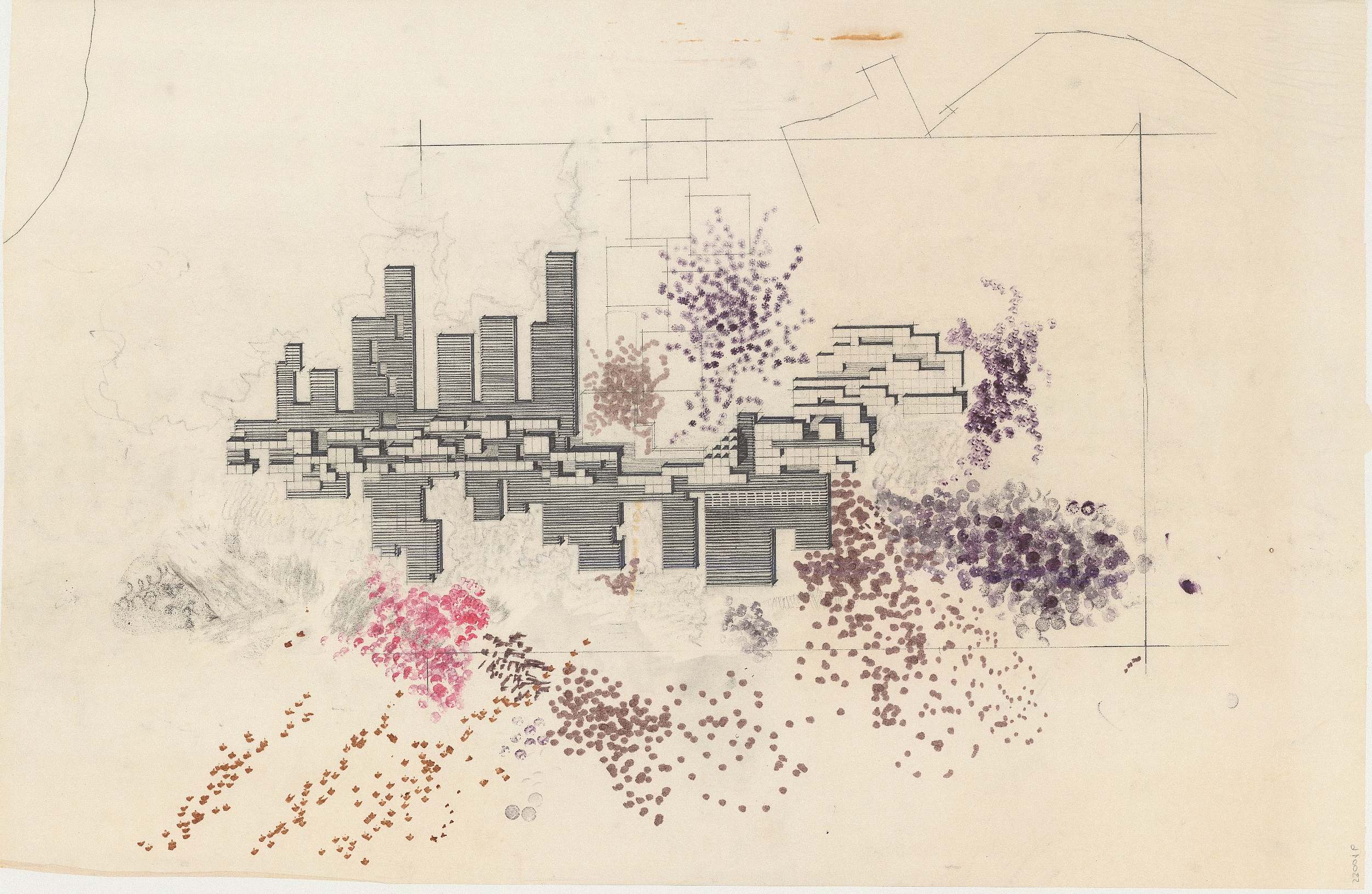

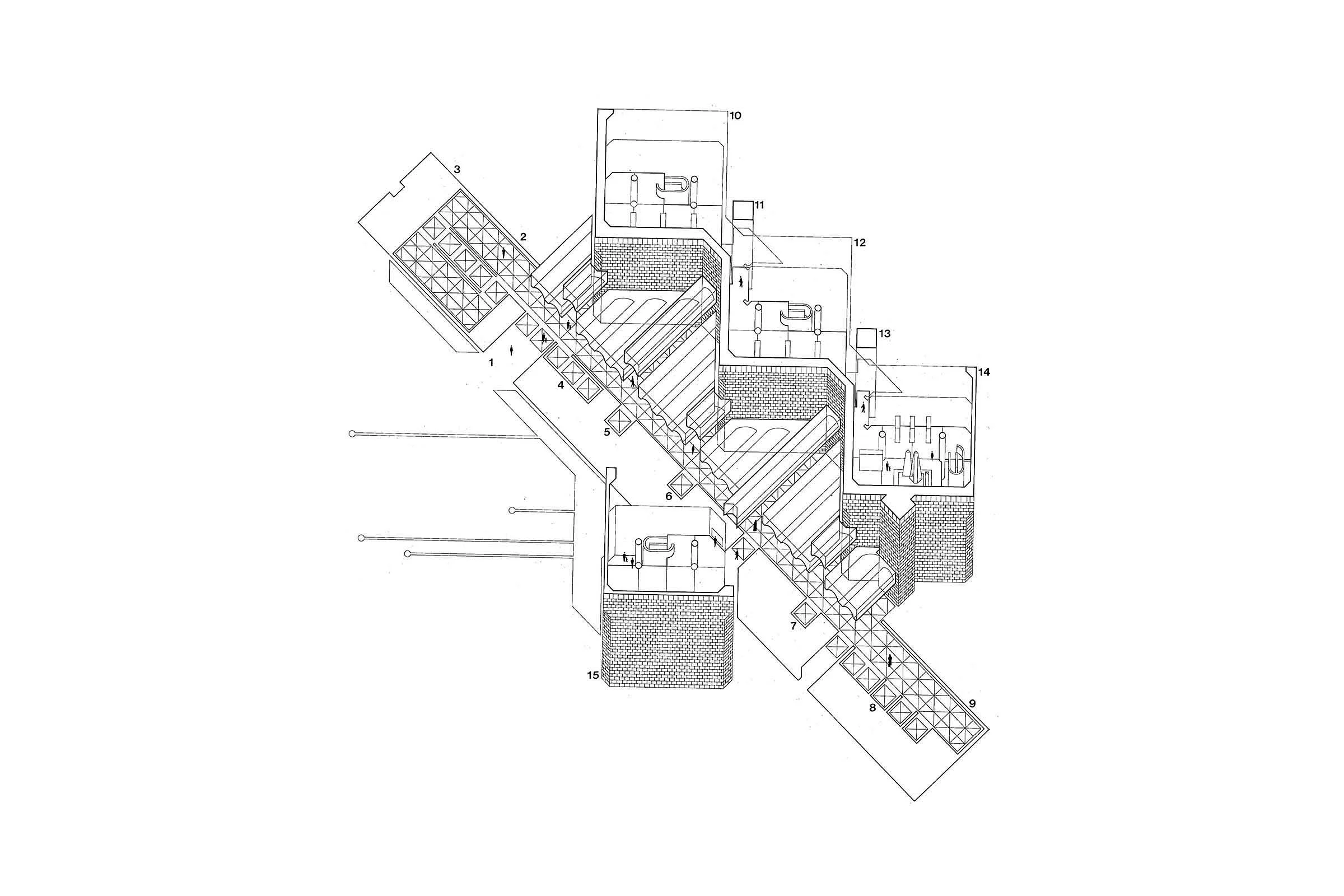

Knud Holscher, who came from Arne Jacobsen's design studio, approached Krohn & Hartvig Rasmussen in the late 1960s. He wanted to enter the competition for Odense University and agreed to become a partner if he won - which he did in 1966. From Arne Jacobsen's design studio, Knud Holscher also brought Svend Axelsson into his new firm to help structure the young architects designing at Odense University.

The structuralist competition proposal for the university, in which the building structure moved when it met resistance and thus wove itself into the landscape, has been a signature of the firm ever since. More recent projects, such as the Haukeland University Hospital, is also based on the principle of maintaining the link with the terrain.

A growing design studio

From Arne Jacobsen, Erik Sørensen and Jesper Lund also joined Krohn & Hartvig Rasmussen's design studio in the early 1970s. At the time, the firm was the largest in Northern Europe, employing 250 people. From the apartments in Langebjerg, the firm designed and built the Technikerbyen in Virum, which they subsequently moved to. In addition to the architectural firm, the large building complex also housed engineering and construction firms together with a large dynamic structure focused on building assignments. It even had its own bus service and kindergarten. The Technikerby was comparable to a large working organism.

Flexibility in the design office

With Knud Holscher's accession as a partner, almost a third design office was created at Krohn & Hartvig Rasmussen. Holscher linked Sven Axelsson and Erik Sørensen to the close collaboration, not least in connection with the realisation of Odense University. With Jesper Lund as his right hand, Knud Holscher worked alongside on design projects in a special sub-department.

The large open spaces of the Technikerby created the best conditions for establishing larger and smaller subdivisions in the large design studio. A flexibility that would prove to contribute to the future organisation of the studio.

Experience in new segments

In the 70's a whole new era of sports and swimming halls started, where Krohn & Hartvig Rasmussen designed Lyngby Swimming Hall, Herlev Skating Hall and Farum Swimming Hall with Knud Holscher, Svend Axelsson and the newcomer Ove Neumann in the lead. The projects were characterised by postmodern tendencies, and the roof constructions were one of the major occupations later continued in projects such as Forum Horsens from 2002-2004 and Helleren School in Bergen from 2007. Here, the large roofs are folded out to bring together all the functions of the rooms below. Since then, the firm has continued to expand its competences in cultural buildings and is today behind several projects both at home and abroad.

Partners say goodbye

Throughout the 70s, the firm said goodbye to its founding partners. In addition to Gunnar Krohn and Eigil Hartvig Rasmussen, John Ryde, Paul Berg and Bent Nielsen also left.

Knud Holscher had confirmed his own department with Svend Axelsson and Erik Sørensen as leading partners. Gunnar Gundersen's department mainly continued the legacy of the time before with follow-ups on Gunner Krohn and Eigil Hartvig Rasmussen's projects.

By the end of the 1970s, Knud Holscher's department consisted of fewer, mainly younger architects and was considered the innovative part of the firm on a daily basis. Daily life here was characterised by seriousness and calm, unlike Gunnar Gundersen's department, which consisted mainly of through employees who had been at the firm for 15-20 years and acted much more casually.

Crisis in the architectural sector

The architectural industry was in deep crisis at the end of the 1970s, and the firm had also been reduced to just 40-50 employees. In the early 70s it had been a workers' market, where as an employee you could pretty much do what you wanted without it resulting in a lay-off, but that changed radically by the end of the 70s, when a lot of younger architects were unemployed. In 1979, however, Knud Holscher hired Jan Søndergaard, who was recruited directly after his graduation from The Royal Academy of Arts School of Architecture. Svend Axelsson subsequently joins the architectural firm as a partner, and Knud Holscher and Sven Axelsson formalize a close partnership.

Despite the great results in the late 1970s, when Tegnestuen won several open competitions, including the New Royal Theatre and the New Town Hall Square in Copenhagen, the projects at that time did not result in realizations. However, the competition proposal for the Royal Palace later resulted in a large extension of the Old Stage.

Bahrain National Museum

Due to the crisis, there were not many major assignments at the design office in the early 80s. However, the previous collaborations up through the 70s with the engineering firm Cowi resulted in the collaboration on the design of Bahrain National Museum - a major new presidential project in the Middle East.

The project was Knud Holscher's major focus, and he placed the newly arrived Jan Søndergaard as outline developer at the forefront of the project.

During the detailed design, a large number of new employees were hired, including Kaj Terkelsen. The project was completed and opened to the public in 1985. In the same year, the design office won the large open competition for Denmark's new National Stadium in Brøndby. The project was the result of close collaboration between Svend Axelsson and Jan Søndergaard, but suffered the same fate as before - the big, beautiful arena was never built.

Postmodernist approaches

In the latter half of the 1980s, the work of the studio was inspired by postmodernist currents.

Jan Søndergaard in his work with the headquarters of Unicon Beton in Roskilde, Svend Axelsson and Jan Søndergaard with Oslo Plads 1, Svend Axelsson with the expansion of Brüel & Kjær in Nærum and the Jægersborg Alle building in Gentofte, Ove Neumann with the Springbanen housing development in Gentofte, Køge Swimming Pool and the Brundland Centre in Toftlund. Gunner Gundersen with the large headquarters for Brdr. Hartmann in Lyngby.

By the end of the 1980s, the firm was again short of work and faced a very serious situation. At the same time, this low point was the beginning of a new story.

New cultures at the design studio

In 1988, Jan Søndergaard, Erik Sørensen, Jesper Lund, Ove Neumann and Kaj Terkelsen joined as partners, together with the newcomer Kurt Schou. Together with Gunnar Gundersen, Knud Holscher and Svend Axelsson, the firm was now run by nine partners and changed its name to KHR AS. With the new partners, several new cultures emerged, which resulted in the firm splitting into several more subdivisions. Internally there were numerous tensions between the departments, but externally there was a single design office.

The Danish Pavilion in Seville

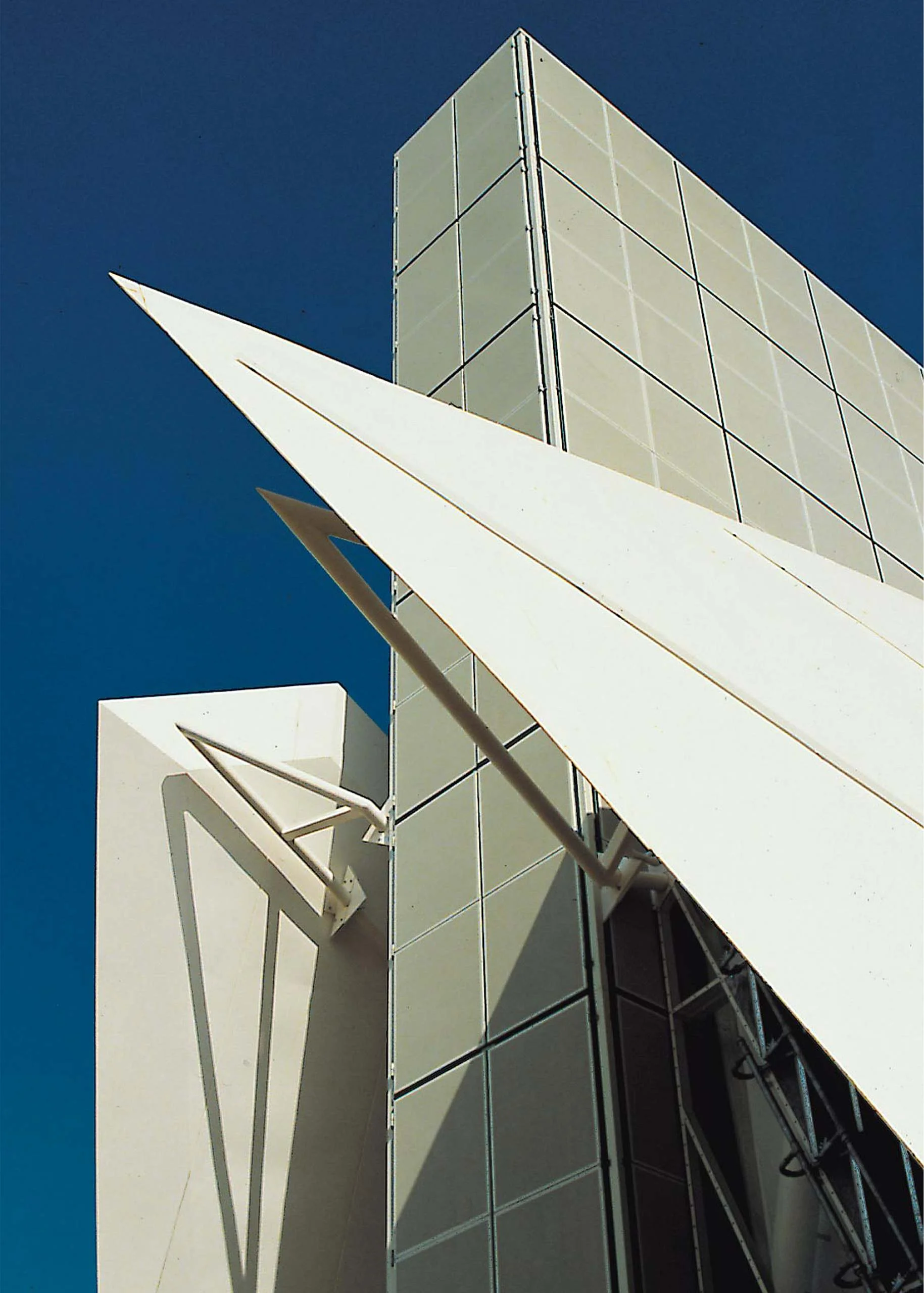

In 1989 Knud Holscher was invited to participate in the competition for the design of The Danish Pavilion at the World Expo 92 in Seville. However, Holscher was heavily involved in developing his own design at the studio and therefore handed the task over to Jan Søndergaard.

This was the start of a smaller department built up by Jan Søndergaard. From the beginning, Jan Søndergaard focused on architecture as a gesamtkunstwerk. This became, then and subsequently, a signature that was expressed as a minimalist reinterpretation of the firm's DNA, not least with inspiration from Odense University. A way of thinking that subsequently came to shape several of the firm's key employees and, not least, its iconic buildings.

Tectonics and architecture as a whole

The pavilion for the World Expo was created through intensive work over two years. Everything was designed and created in individual parts, shipped to reduce energy consumption, and only assembled in Seville in time for the opening of Expo 92.

The Seville Pavilion was conceived as a sculptural and unique tectonic architectural gesamtkunstwerk. The project was noticed and received great international recognition for its holistic approach to thinking about technology and architecture as a whole and for creating a sustainable exhibition building without energy consumption. The building became living proof that Danish architecture sprang from an ability to optimise and hone the art of building.

A new era

At the start of the 90s, the general picture at the design office was one of a great lack of assignments. This led Erik Sørensen and Jesper Lund, together with the old partners, to focus on finding new assignments within infrastructure. The firm had experience in this field, having designed and built both Copenhagen Airport's office building and Finger B in 1986 and the Domestic Farm in 1998.

This resulted in a successful renewal of working areas with roadways and bridge structures on both sides of the Sound in connection with the new Øresund Bridge. This launched a new era, with the firm continuing to compete for work at the expanding Copenhagen Airport.

From crisis to a new signature

Svend Axelsson managed to persuade the airport management to let KHR AS organise competitions at the design office, where five teams drew against each other for the development of the airport. With Erik Sørensen in the lead, the firm designed and built the parking garage at the foreign terminal in 1990-1991, which became the forerunner of a number of subsequent parking garage buildings.

After a deep crisis, infrastructure suddenly became a new signature for the design studio. Since then, the firm has been behind projects such as Finger D in 1996-1999 and security control from 2007 at Copenhagen Airport and the expansion Pir F at Arlanda Airport from 2008 Led by Jesper Lund, and not least the later Copenhagen Metro.

Break with postmodernism

The beginning of the 90s marked a break with postmodernism and a return to the original DNA of the studio. Inspired by his work on the Seville Pavilion and his many stays in Spain, where neo-modernism had its breakthrough in the early 1990s, Jan Søndergaard designed the new headquarters of the construction company Pihl & Son in Lyngby. The last phase of three extensions was inaugurated in 2007.

The relatively new arrival Henrik Danielsen joined the process, and it was the beginning of a unique collaboration based on bringing together the architectural idea with the practice and reality of the process to perform at the highest level.

Cooperation leads to new projects

Everything at Pihl & Søn was uniquely designed into the project from the whole to the detail, from landscape to building parts to the smallest fixtures. The building was technologically inspired by the Seville project and was thus the first administration building based on passive solar heating and natural ventilation.

The ongoing collaboration with Pihl & Søn resulted in Jan Søndergaard being commissioned to design a new headquarters for Istak, Pihl & Søn's subsidiary in Reykjavik. The project was realised in collaboration with Henrik Danielsen. The project achieved national recognition at its inauguration in 2001.

Landmark, listed building

The Pihl & Søn building set the tone and reintroduced modernism in Denmark, but in a simpler and minimalist version - minimalism. The large windows open up varied sensory experiences throughout the day. The project drew on several of the firm's earlier signatures, where the clearly defined form is dissolved again and again to be experienced as a whole of composite alternating spatial intimacies in an interplay between building and landscape. The building, with its 7,000 m2, emerged as an architectural whole and in 2015 was recognised by the Danish Agency for Culture and the Arts as a unique gesamtkunstwerk and has therefore been declared a listed building.

In the mid-90s Knud Holscher, Ove Neumann and Gunnar Gundersen left KHRAS, and Nille Juul-Sørensen became a new partner.

A special signature

Seville was the start, but Pihl & Søn formed the actual basis for the further work in Jan Søndergaard's department at the design office, with alternating associates who contributed to the special signature.

After Pihl & Søn, Jan Søndergaard designed the extension to the Danish Embassy in Moscow, inaugurated in 1997. The project was realised in collaboration with Henrik Danielsen, who was now a permanent employee in the small department.

Enhanced cooperation in the commercial sector

The department was expanded during the design phase with the addition of young architect Mikkel Beedholm. Jan Søndergaard subsequently designed the new Headquarters of Bang & Olufsen. The project was realized in collaboration with Henrik Danielsen and Mikkel Beedholm and was inaugurated in 1997.

Similar to the previous projects from the small department, the composition of the group's competences resulted in high architectural quality and a focus on the realisation of the projects according to the agreed construction budget. The success of the project resulted in an extended collaboration with Bang & Olufsen. Initially the development of a new Worldwide store concept, which resulted in the design of 32 stores globally with Mikkel Beedholm at the forefront. Interiors and fixtures were designed to encourage emotional interaction with the products on display.

Cooperation with Bang & Olufsen continued with the design and realisation of the new production plant Medicon in Struer. The project was realized in collaboration with Henrik Danielsen in 2001.

Sustainable architecture with good indoor climate

Characteristic of all the projects of this period was that they united architectures and tectonics into a sustainable whole. Sevilla Pavilion's simple cooling technology designed as integrated displacement and construction thermics, Pihl & Søn's thermal indoor climate via natural ventilation combined with passive solar heating, Bang & Olufsen's further development of the principles into a hybrid solution and Istak, as a combination of the previous models in a summer and winter design.

Culmination in infrastructural construction

In 2002, KHR AS changed its name to the now well-known KHR Architecture, and Svend Axelsson, Nille Juul-Sørensen and Erik Sørensen left the firm during that period. In 2003, Jacob Brøndsted joined as a partner along with Anja Rovlung and Mikkel Beedholm, who had been part of Jan Søndergaard and Henrik Richter Danielsen's department since joining in 1993.

During the 00s, the firm's previous experience in infrastructure culminated in the construction of Copenhagen Metro. A large team from KHR Architecture designed and developed plazas and spaces in the city, juxtaposing landscape space and tectonics in the context of construction. The major focus was on daylighting, where skylights help to connect the two worlds above and below ground and help to create a safe and secure journey for passengers.

Renovation with respect for the architecture's origins

The studio also designed Ballehvileren and Metrouret, which can be found at the Copenhagen metro stations.

KHR Architecture has continued to develop its skills in the field of infrastructure construction with the two major metro stations, Malmø Lower and Triangle in Malmö and the thorough renovation of Østerport Station.

Østerport station is a listed building, and the renovation was therefore carried out with respect for the architectural origins, but also with a focus on modern building requirements. The use of materials similar to the originals has therefore been essential to preserve the integrity. The renovation and architectural work was carried out in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture.

Using new materials with transparency

Inspired by the Seville Pavilion's successful use of fibreglass in the design of the main sails, Jan Søndergaard Holy Cross Church in Jyllinge. The idea here was to use the transparent properties of fibreglass in the design of the spiritual church space.

Simply explained, the divine was to emerge from a combination of the church's transparent ceiling to the sky and the large light opening that framed the view over Roskilde Fjord. The space was to unite the heavenly with the earthly. The church was inaugurated in 2010 and has become the focal point for many cultural activities, not least concerts.

A tectonic whole

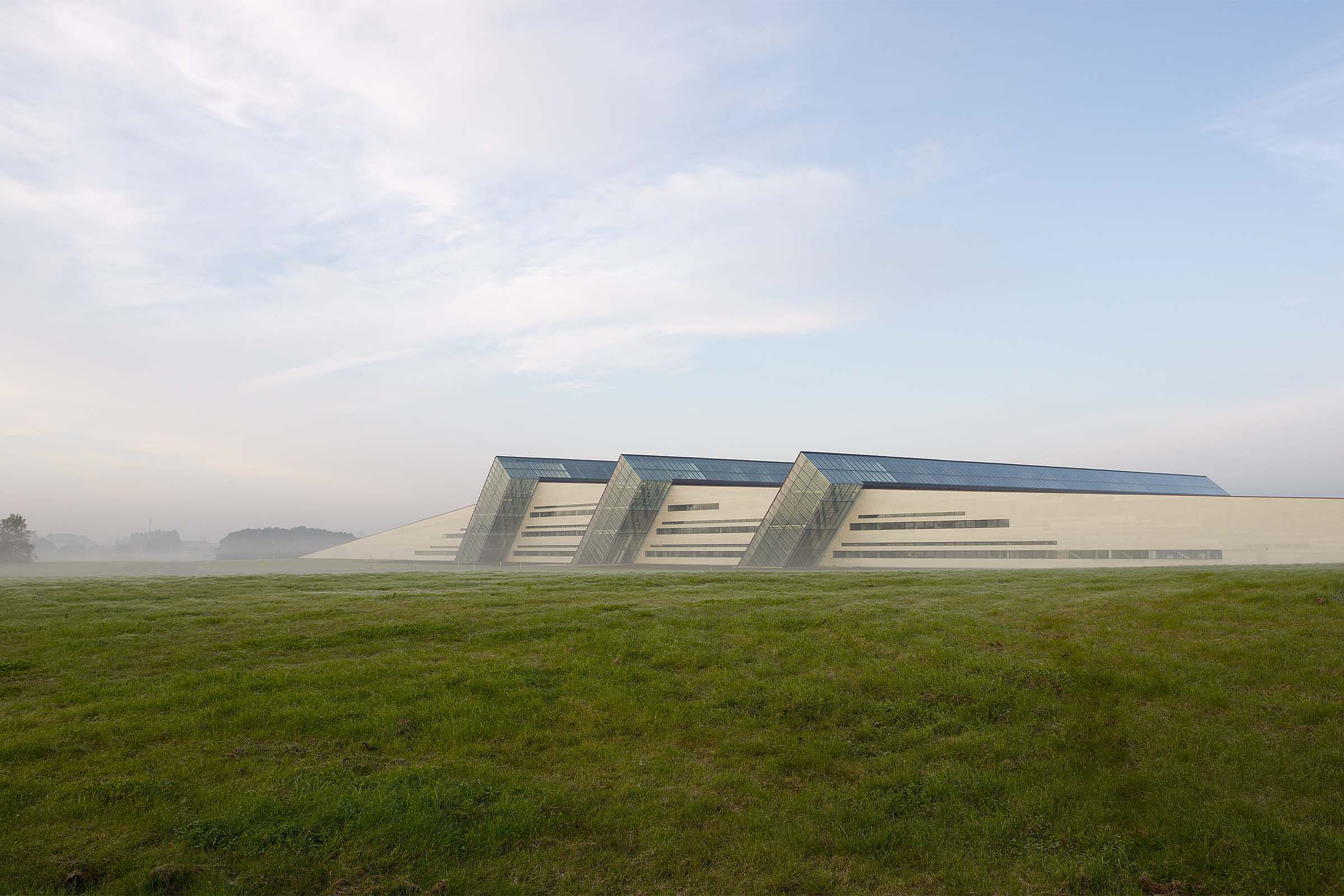

The close cooperation with the glass fibre producer resulted in the request for the design of a new factory for Fiberline in Middelfart, realised by Jan Søndergaard in collaboration with Henrik Danielsen.

As with the previous projects, technology and architecture were conceived as a tectonic whole. Unlike the vertical pipe penetrations normally associated with factory buildings, all the necessary installations were integrated into the sunshielded south-facing surfaces of the skylights.

A laboratory for innovative educational construction

The drawing office functioned as a kind of laboratory throughout the 00s. Jacob Brøndsted was looking for new ways to think about primary schools, and it started a new era of focus on educational building for the design studio. Utterslev School, designed and built from 2000-2003, became the most outstanding example of this innovation in the period. The school's structure and organisation brought together school and leisure, and broke down the traditional subject areas.

It was also in the noughties - in 2006 - that KHR Architecture moved to its current premises in the Gunboat Sheds on Holmen.

Cooperation in the education sector

In the late 00s, respectively. Jesper Lund, Kurt Schou and Kaj Terkelsen as partners, and Henrik Danielsen joined the partner group consisting of Jan Søndergaard, Mikkel Beedholm, Anja Rovlung and Jakob Brøndsted.

Jacob Brøndsted and Mikkel Beedholm drew together at the internationally renowned Ørestad Schoolwhich, from the children's perspective, should create the best environment for play, learning and socialisation. KHR has since been behind KUA from 2010 and entered into cooperation in the education sector with the PPP projects (Public Private Partnership) Vildbjerg School at Herning and Ørstedskolen on Langeland.

Architecture in an Arctic Climate

KHR has also made its mark in educational and cultural construction abroad. With Greenland Institute of Nature as the starting point in 1998 and Hans Lynge School in Nuuk from 2011, the firm has expanded its skills in designing architecture for an Arctic climate, where materials and design safeguard the building against weather conditions while integrating it into the landscape.

KHR Architecture has since continued to work in Greenland with among others. Nuuk Schoolwhich is now under construction. Leading the work in Greenland is partner Janina Zerbewho has been part of KHR since 2015. Janina Zerbe is involved in all of KHR's recent projects in Greenland and is familiar with the unique nature that needs to be taken into account when building in an Arctic climate.

Artistic development work

In 2019, Jan Søndergaard left the partnership, but remains a senior partner, combining his artistic development activities as a professor at the Royal Danish Academy with architectural research at KHR Architecture. The work involves both PhD scholarship holders and students who contribute to the practice both challenging and developing the creative practice of architecture.

Strengthened international presence

Since 2013, engineering graduate Lars Kragh has been CEO of KHR Architecture, and the firm has focused on strengthening its presence abroad. In addition to projects in Greenland, the firm has also entered the German market with The school at the wide gap - a school in Berlin for 725 pupils, which is under development. In addition, KHR Architecture has strengthened its presence in Norway with Amalie Skram Further Education School and AdO Arena in Bergen from 2014 and Children's and Adolescent Hospital in Bergen, where the second phase is about to end.

Increased focus on sustainability and innovation

KHR is known for creating innovative, long-lasting architecture where users and context are at the centre. Perhaps because of its more than 75 years in the industry, KHR recognises the potential and necessity of making architecture ready for the future. The legacy of projects at home and abroad that are still beautiful and functional today is the best business card.

At the same time, the organisation, headed by Cameline Bolbroe, has a dedicated department that systematically ensures a focus on sustainability and innovation in processes and projects. The most sustainable building is the one that is never built, which is why architecture must be forward-thinking.

New partners and a business on three legs

Since a reorganisation in 2022 after a difficult time through Corona, KHR has been led by the six old and new partners Janina Zerbe, Henrik Danielsen, Mikkel Beedholm, Lars Kragh, Peter Nielsen (new) and Torben Juul (new). In contrast to the days of numerous partners and internal groupings, the studio now has a common ground in both the business strategy and creative decision-making processes.

With the new group of partners, the business was simultaneously focused on three main areas; the old core competences, health and educational building to the public sector, Housing- and commercial building in private and public sector organisations, as well as the relatively new business area building consultancy with derived benefits such as urban planning work, space planning and transformation.